► New petrol and diesel sales ban set for 2030

► Taxation shortfall as EVs gain popularity

► Road pricing might not result in better roads

After years of Westminster chatter, it appears as though road pricing is gaining favour among senior government figures as a means to bridge the taxation chasm set to be caused by the ban on new combustion-engined car sales from 2030, according to a report in The Times.

Prime minister, Boris Johnson, has confrimed that the cessation of sales of brand new petrol and diesel cars in the UK, is being brought forward to 2030. Only plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) will be given a reprieve, but even then only until 2035.

Zero-emission vehicles, using electricity or hydrogen fuel cells, are welcome news for the environment, but a forecasted sharp decline in petrol and diesel fuel sales would hit the country’s coffers hard.

How big could the tax shortfall be?

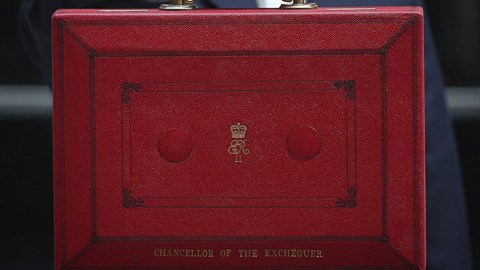

Essentially, the chancellor Rishi Sunak has a potential £40 billion taxation revenue dilemma, which is why – according to the paper’s claims – he is warming to the idea of drivers paying for using roads as a way of balancing the Treasury’s books.

That £40 billion estimate is derived primarily from the loss of fuel duty, but also VAT on the fuel and VED car tax, something only presently paid on new zero-emission cars where they cost over £40,000 new.

Given the devastating economic impact of COVID-19 – Britain’s expected budget deficit of at least £400 billion in 2020 is the worst in peacetime – plus the potential for further financial pain resulting from Brexit, this is a problem the chancellor would rather not be facing.

How could road pricing work?

Given that we’re still the best part of a decade away from the ban on new petrol and diesel cars, the chancellor is in no immediate rush to finalise exactly how road pricing could be implemented.

It’s unlikely that cars will be fitted with black boxes or windscreen tags that record their every movement given the privacy infringements attached to such a move, but given those plus automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) systems already exist, such technology could be used to charge motorists for entering urban zones – as is the case in Central London – or particular types of roads, such as motorways.

Currently, the M6 Toll motorway is Britain’s only stretch of pay-to-use highway, although various crossings, such as the Humber Bridge, also charge for their use.

Who will pay for road pricing?

At this juncture it’s too soon to know whether the road pricing levy would be something paid exclusively by electric- and hydrogen-propelled motorists, or if fuel duty could be removed completely with all drivers being charged under the same system.

Given that many of Britain’s more rural communities tend to be Tory-leaning in their collective politics, the government will be keen to ensure that residents in small towns and villages where there is little or nothing in the way of a public transport infrastructure are not disadvantaged by any road pricing legislation.

Not charging drivers to use minor A-roads and B-roads might have some appeal, but it’s wrought with problems, not least traffic levels on such routes would likely increase significantly as people try to avoid fees elsewhere.

Additionally, many of the nation’s roads are blighted by broken surfacing and potholes. Whether any road pricing measures would contain a degree of ringfencing to allocate funds for reparations is up for discussion, but is unlikely given that presently VED and fuel duty are not used for this purpose.

How do you feel about the prospect of road pricing being introduced nationally in the UK? Let us know in the comments below